Posts relating to arts projects (writing, curating, etc.)

-

In from the Garden

“Half the interest of a garden is the constant exercise of the imagination. You are always living three, or indeed six, months hence. I believe that people entirely devoid of imagination never can be really good gardeners. To be content with the present, and not striving about the future, is fatal.” – Alice Morse Earle (1897)Twentieth century German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys famously proclaimed “every man is an artist” and it seems that we have built upon this notion to include craft practice. It is perhaps easy to utilise Beuys’ statement as a truism for considering all creative practice as equivalent but the realities are much different. For the majority of us, one reminder from our time spent making is the sobering discovery that the vision and skills necessary to realize a well crafted object readily identifies the ‘amateur’ from the ‘auteur’.

Art, including craft is a barometer of the times, and as Alice Morse Earle observed, notable practice always looks to the future. Gleaning information about the practices of a new generation of contemporary craft artists, In from the Garden showcases four currently establishing makers who clearly have strived for the future, both creatively and professionally. These exhibitors, since emerging from their respective New Zealand tertiary arts programmes during the last half decade, have between them exhibited nationally and internationally, entering and winning awards and demonstrating capabilities as makers of artistically attuned craft.

There is a certain period in a creative practice where a maker has attained that fine balance between exhibiting and selling work, making a living and having time in the studio: i.e. the realities of professional creative practice. During this period, where there is often much more to achieve, there is a sense that an epochal work could be just around the corner. Objectspace has observed the opportunities and difficulties makers can encounter in establishing practices. With this in mind, In from the Garden is intended to look closer at four makers from around New Zealand who, currently at this period of their respective careers, are staying the course and readying to settle in for the long haul.

A new series of work by jeweller Renee Bevan goes by the boldly self-explanatory title, Blooming Big Brooches (2008-9). One can confidently claim that Bevan is currently obsessed with flowers. Bevan recalls, “I have long been fascinated with the pre-packaged emotive power of flowers; specifically the rose. Its manufactured sentimentality, vast symbolism and long-standing history in jewellery and adornment; the rose has a unique ability to speak of love, life and death all at the same time. Transforming imagery and materials already entrenched with an abundance of history and meaning I exaggerate and play on their existing connotations and suggestions.”

These brooches engage in a distinctive new conversation for Bevan regarding dimension, subject and adornment. Earlier in her career, Bevan was fascinated by pre-existing jewellery. A series of work entitled Lost and Found (2005) resulted from casting new works in precious metals as direct impressions from mass produced jewellery. (1)

This time around, Bevan has borrowed generic images of roses, the kind of images which proliferated in 1960s and ’70s gardening related publications. In these new works, the rose image is détourned, (2) cut-and-pasted to become sections of petals on successive layers of wood. The resulting brooches are kind of clunky yet elegant and not entirely disposed of their former glory.

Ceramic artist Blue Black is engaged in a practice which emerges from “an organized and ordered place to disorderly, freeplay chaos and back to organizing what happened.” Embodying these words, Black’s works arrive from the kiln as perlocutionary statements after this energetic and performative process as variously charred, colourful, grotesque and ultimately striking objects.

Blue Black’s work is refreshing at a time when it often seems every aspect of the craft process is over-investigated for relevance in order to be vindicated, sometimes stifling free expression. Black tackles expressive processes with relish explaining that “while my imaginings take a back seat the physical pleasure of the actions of making is the focus … My priority is finding my own rhythm and being swept along in the sensations of the body and materials, as if it is a performance.”

Through the study of expression, Black’s research forms an organic part of ceramic practice. Pushing clay around freely is championed and thus allowed to inform the artist’s thinking about modernist concepts like the sublime and the subconscious as something “produced from automatic emotional responses of the artist which can be perceived by the viewer.”

In Harm’s Way? (2008) is a central work for Jeweller Victoria McIntosh, who presents this installation with the quote, ”Primum non Nocere – First do no harm.” A maker of finely crafted individual works and installations, McIntosh’s work often seems to poke at the vagaries of how we each relate to objects and in the process of doing so emotionally attach ourselves to them, using this emotional resonance to draw meaning and define our notions of individual identity.

A provocation is deliberately set-up and ’emotionally fractured’ in In Harm’s Way? by McIntosh. A collection of found and hand altered finely crafted objects are subjected to the notion of separation – a central idea in McIntosh’s practice, as an adoptee. In this work a framed found image depicts a mother and child. This image, with its cracked glass metaphorically separating the two intimate subjects, is installed beside a matching frame containing various objects. The words ‘Nature’ and ‘Nurture’ are finely embroidered onto the labels of two vintage lace collars, subtly embodying the dichotomy that may come to bear if we are separated from our genetic past.

Echoing Alice Morse Earle’s observation, McIntosh is concerned with the future, as she observes, “science moves us further away from the tried and tested methods of conception – I am left wondering the impact this will have on future generations. The concerns I have stem from my experience growing up as an adoptee without access or knowledge of my own genetic origins. This piece is a response to the new reproductive technologies and the ethical questions they raise for society as a whole.”

Ben Pearce’s practice illustrates the value of tinkering around in the studio with conceptual ideas and technical craft skills ready to be freely deployed. Pearce’s objects are predominantly of wood, which is minutely crafted and skillfully combines locally found objects and machine parts.

Pearce is inspired by memory and childhood. For Pearce childhood is a metaphor for the act of looking at something potentially unknown, as an adult. A recent work, 28 Various Preservations (2009) delved into this idea in depth, with Pearce noting “28 actual memories may be recalled and visited here, just one small section of a vast inter-related city. A City of desperation and adaptation, the forms are not eloquent or fancy, they take on a tree hut feel, that of ingenuity, as if constructed simply to perform a basic function of protection.”

Similar in some respects to Victoria McIntosh, Pearce is also interested in family history and genealogy but from a more general perspective. A recent work, Grandfather Clock (2009) “presents a window into the idea about the connections that we make and construct around an ancestor un-met. The pieced together nature of information that in-stills in us a type of familiarity of them, we wish to meet them face to face, stand in their air and time.”

The makers in In from the Garden emerged from educational programmes developed in the 1980s for an art sector which has evolved since then. A number of New Zealand tertiary institutions have expressed a reinvigorated level of enthusiasm towards craft in the two ensuing decades. This is in no small part due to the successes of a select group of New Zealand craft-aligned artists gaining international recognition. Some of these makers trained in the above programmes, along with mid-career makers who emerged earlier.

Accommodating for and building upon the interest in a small but vital and expanding field like contemporary craft requires not only innovative ideas but also forward thinking at an educational level. Despite certain regional strengths within disciplines of craft education, care is needed to develop and ensure existing programmes stay relevant. The perceived strength of craft programmes is on one level the opportunity for students to acquire craft skills and on another level the opportunity to refine their critical (fine art) acumen: there is often an issue with the balancing of these two dimensions. (3)

The four makers in this exhibition have established a strong case for the continued valuing of craft skill. Without a place to learn these skills, aspiring makers in craft disciplines have limited options outside of established community-based societies. It is a concern for many that some institutions are moving towards combined art and design programmes, where the balance between theory and practice does not address the distinctive nature of craft practice and the needs of emerging practitioners.

The context for making contemporary craft and art is an intimate occasion, drawing upon makers wants, needs and concerns and it is a natural conclusion that these makers are often drawn to the deepest recesses of their imagination. These unique vantage points are a rich source for rewarding and enlightening projects. Helping to redefine the parameters of contemporary craft and fine art practice, the makers featuring in In from the Garden demonstrate that they are “striving about the future”.

Matt Blomeley

28 May 20091. http://www.objectspace.org.nz/programme/works.php?documentCode=656 (26 May 2009)

2. A fine arts technique where imagery, or an object, is borrowed or reused to make a new work; often containing a different message than intended by the original author.

3. Jenkins, Douglas Lloyd, Volume: After The Makeover, keynote presentation, ‘Volume’ symposium, Hawkes Bay Museum and Art Gallery, Napier, 18 October 2008, http://www.hbmag.co.nz/item/volume_dlj.pdf (26 May 2009). Jenkins’ notes that this emphasis on degree credentials at the expense of skills is not limited to New Zealand and he quotes Jane Jacobs, who has cited a similar concern within the diploma system in Canadian community colleges.

Image – Ben Pearce, Home Alone No. 2, English Beech, English Walnut, Cotton, 2009, courtesy of the artist (image Peter Tang)

———————————

What: In from the Garden curated by Matt Blomeley

Where: Objectspace, 8 Ponsonby Rd, Auckland

When: 6 June – 18 July, 2009

Gallery hours: Tues – Sat, 10am – 5pm. Free admission. A print publication for this exhibition is available from Objectspace. -

Mind the Gap

There is no reason to deny the reality of progress, but there is to correct the notion that believes this progress secure. It is more in accordance with facts to hold that there is no certain progress, no evolution, without the threat of “involution,” of retrogression. Everything is possible in history; triumphant, indefinite progress equally with periodic retrogression. (1)

– Ortega y Gasset

Observed from a distance the earth’s landscape and our interventions upon it are at once mysterious and obvious. Modern technologies such as GPS devices combined with satellite imagery allow us to navigate land and ocean in unprecedented detail. Whether it be obtaining navigational directions to the supermarket or ‘geotagging’ hiking adventures over distant mountains, we now more than ever before perceive the landscape topographically. From this unique perspective areas of mystery from past eras are exposed to us conclusively, in photographic detail. Unresolved details of the land have become more or less reduced to heavily vegetated areas, along with vertical terrain and the underground.The quality of topographical imagery available varies considerably within popular web applications, most notably Google Earth. Enticing our imagination to complete unseen spaces, the flaws and imperfections in these images highlight the limits of photography (at least the limits of imagery we are allowed access to in the public domain). In a sense, working from these images offers a ‘plein air’ painterly pretense for the painter, who is engaging with the outside world but at one remove from the traditional model of an artist towing his or her easel through a field.

Gaps have at one time or another invoked imaginative responses in us all. Whether it be cracks in the pavement or the narrow spaces between domestic decking floorboards. In this new series of paintings, Adrian Jackman is considering gaps in the landscape. Investigating the agricultural technique known as circular irrigation, two of the three paintings in this exhibition, entitled Detail, and The Fall, refer to an ongoing discussion for Jackman whose earlier works occasionally explored the landscape from a similar point of view. Relating to his works which were based on the manicured landscape of golf course fairways, these new paintings observe the land similarly, but this time tended on a massive scale for agriculture.

Describe circular irrigation to most people and they will no doubt recall the crop circles depicted in Hollywood extraterrestrial films and conspiracy theories. Circular irrigation is easy enough to explain as the pattern created by massive irrigation sprinklers. Jackman’s physical brushstrokes suggest a Courbet-like approach (2) echoing against the impermanence that we see in satellite photographs of these assembled landscapes. Rough painterly gestures in certain areas are contrasted with carefully measured lines and sections of sfumato (3) indicating where the photographic image fails to capture the details.

In these fields seen from directly above there is no qrandiloquence of nature, as in old paintings; the sublime is replaced by a matter of fact, topographical view of our invasion upon the land. Looking closer, the arrangement of forms appears hastily constructed. Roughly slotted in between arterial roads, circular crops take in as large a space as they are able. In most fields the irrigation circle is only partial and missing sections of the pie shape are taken up by conventional rectangular paddocks and buildings. These abstract and slightly haphazardly arranged shapes are perhaps epithets, for Jackman, of our engagement with nature.

The titles of the two larger scale works (Detail and Inset) in Jackman’s exhibition deliberately borrow straightforward photographic terminology. These titles, lowly technical definitions in the realm of photography, imply a conditional status upon the works, in effect freeing painting from historical jargon inasmuch as they suggest the potential importance inherent in any image, photographic or otherwise.

With the largest work, Inset, the topographical idea that initiated the series appears to have been exorcised and provides Jackman licence for a new investigation in the same theme: tractor tyres. While Detail and The Fall depict and also abstract the images of our interaction with land, Inset goes one step further in arranging a pile of future archaeological objects.

Taking in the visually jarring effect of a pile of tyres forming the monochromatic composition of Inset – a large map-like painting spanning numerous linked-up sheets of paper – brings to mind the work of 1960s optical artists. While that is partly a historical refence by Jackman, this work belongs to his on-going drawing practice, which operates alongside and occasionally conjuncts into his painting practice. Possibly inspiring or challenging a new direction for Jackman’s current investigation, Inset is in effect a counterbalance to the two topographical paintings; the detritus of agricultural machinery forming an emblem for this project.

Matt Blomeley

Tuesday, 17 March 2009Mind the Gap will be on show at Lopdell House, 18 April – 24 May 2009.

(Satellite image courtesy Adrian Jackman.)

Adrian Jackman website http://www.adrianjackman.com/Footnotes:

1. Ortega y Gasset, José, The Revolt of the Masses, W.W. Norton and Co, New York, 1930 (1993). (pp79)

2. Harrison, Charles, Conceptual Art and Painting: Further Essays on Art & Language, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2001 (pp85,86). Harrison discusses Fried’s study of Gustave Courbet, interpreting the physical nature of Courbet’s painting: “Foremost among the defining preoccupations of Courbet’s work, Fried diagnoses an urge – necessarily and significantly doomed to frustration – to transport himself bodily into the painting taking shape, and thus to close the gap between painting and beholder … Courbet’s attempt to eliminate the distinction between painting and painter beholder is seen by Fried as a means to defeat theatricalization, and thus preserve the integrity of modern painting.”

3. A painting technique of merging multiple colours without a hard edge, sfumato is derived from the 19th century Italian definition which literally translates as ‘shaded off’. -

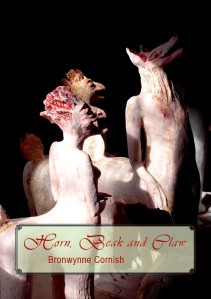

Indian Fortunes: Bronwynne Cornish

A favourite holiday novel of mine returned to several times over the years is set in an idylic university town. There is of course something asmiss with this place, not that many locals would even notice: a powerful spiritual presence lingers in the surrounding landscape. To the few who are destined to see it, this admirable yet malevolent looking character takes the form of a giant black domestic cat, cursed by a local witch to linger around the town and its surrounding hills. (1)

The spell which binds the old tomcat to the town is also an invisible leash, occasionally tripped over when visitors to the town and locals happen to cross his path. The central character in the story becomes entangled with the cat in this manner. She meets him again after passing to the ‘other side’ and, upon discovering his endless multitude of physical forms, has the following conversation with him: “ ‘Schrödinger’s cat!’ ‘That’s only a concept, more than that.’ Was it against the law of the universe for anything to be only what it seemed? ‘Nothing is against the law. The law is its own violation. That is the core of all events, that is Schrödinger’s cat.’“ (2)Heavy dialogue for a popcorn novel, which no doubt passed right over my head as a teenager. I was surprised, in returning to the novel recently that it would actually have some relevance to me as an adult reader. The common superstition, explored in this novel, that we are predestined to a certain path (that can even account for when fortune or misfortune prevails upon us and we are confronted by our ethics in making decisions!) returned to me upon visiting Bronwynne Cornish’s ceramic studio and considering her most recent work.

Fortunate to undertake a 2008 residency in India, this experience has greatly influenced Cornish. Speaking about one of the repeating forms that is due to feature in her 2009 exhibition at Masterworks gallery, she relayed to me the story of a remarkable place in India, which she was unfortunately unable to visit first hand during her time there, for logistical and geographical reasons. In this place is a library that apparently holds a detailed pre-written record about anyone who wishes to know their path or fortune in life.

Cornish’s shapeshifting works, related to the story she told me – reminding me of the karmic premise as well as the imposing creature of my novel – are a series of six legged beings. Standing proud on four solid, powerful looking legs, their arms with palms cupped together servant-like hold forth your fortune cards. Although there is an overhanging air of mysticism to these works, Cornish is offering more than just an effigy of ethereal worlds and beings. Her investigation also concerns the present, the future, and our place in it.

The maker of ceramic objects which literally wear the skin of her subject(mysticism), like an unbiased contemporary theologian holding the subject of religion at arms length, Cornish explores in-depth and with an open mind the desperation with which we sometimes cling to beliefs and presumptions that have been held for millenia, all the while looking for underlying questions. The questions, and possibly answers, that Cornish is posing with these works are deliberately left open for the eyes and minds of the viewer to ponder and decode, as she is not presumptuous enough to suggest otherwise.

Of any subject or idea that comes to mind upon considering Cornish’s new works, perhaps the most important is the notion of Self. Philosopher Slavoj Žižek observes that “if we penetrate the surface of any an organism and look deeper and deeper into it, we never encounter some central controlling element that would be its Self, secretly pulling the strings of its organs … there is effectively no self … A true human Self functions, in a sense, like a computer screen: what is “behind” it is nothing but a network of “selfless” neuronal machinery.” (3)

To know that ones Self is not governed by something other pulling its ‘strings’ is refreshing, yet it does not negate the enjoyment of lyrical objects, which often engage in a language that predates western science and philosophy. Cornish’s works operate interestingly and fluently in this context; contemporary objects – enjoying a growing, appreciative audience – in an age where it is more common to see artists exploring science and genetics than pre-European belief systems.

Bronwynne Cornish’s years of pushing clay through her fingers are combined with intriguing ideas and relevant subjects to make a convincing artistic statement, reminding one that we each exist as a conflation of our bloodlines and our learned experiences. As Žižek notes, “what makes me “unique” is neither my genetic formula nor the way my dispositions were developed due to the influence of the environment but the unique self-relationship emerging out of the interaction between the two.” (4)

Matt Blomeley

8 March 2009Essay commissioned for Bronwynne Cornish’s upcoming exhibition Horn, Beak and Claw at Masterworks)

1. Strieber, Whitley, Cat Magic, Grafton, London, 1988.

2. Ibid. (pp323,324)

3. Žižek, Slavoj, Organs Without Bodies, Routledge, New York and London, 2004. (pp117,118)

4. Ibid. (pp118) -

Head in the Clouds

Phil Cuttance says of this work, “Similar to the rough diamond (another recent Cuttance lightshade), the cloud city shade’s pattern was inspired by simple pop-up book patterns. This shade is created by cutting and then folding flat shapes to create the volumetric form of a mythical ‘cloud city’.” Since graduating in 2002 with honours in Industrial Design from Massey University, Cuttance has established a unique brand of quirky and quick witted design objects for production. Lightheartedly describing himself as a “design bogan”, Cuttance pays homage to this Australasian social archetype with an impressive variety of works which have been exhibited in Auckland, Sydney and Milan. Having moved to London in early 2009 to further his career, we can expect big things from this talented young Kiwi designer. www.philcuttance.comMatt Blomeley, 6 March 2009

-

Renee Bevan’s ‘Blooming Big Brooches’

A recent series of work, by New Zealand jeweller Renee Bevan, goes by the boldly self-explanatory title of Blooming Big Brooches. One can confidently claim that Bevan is currently obsessed with flowers, “specifically the rose; its manufactured sentimentality, vast symbolism and its long-standing history in jewellery and adornment.” These brooches, soon to be exhibited at Inform Contemporary Jewellery in Christchurch, engage in a distinctive new conversation regarding dimension, subject and adornment. Renee Bevan is at the forefront of a new generation in Australasian jewelers. Having graduated in 2002, her work has been featured in a number of important exhibitions at institutional project spaces and dealer gallery’s over the past few years, culminating in her selection for the international jewellery exhibition, “Schmuck 2008”.Image: “Bill Riley wearing Blooming Big Rose Brooch,” courtesy Renee Bevan

Matt Blomeley, 6 March 2009 -

Kate Barton: 2D/3D

This window installation for Objectspace embodies a form of duality, in both a literal and a critical sense. Kate Barton studied as a contemporary jeweller before following this up with studies in animation. Fittingly, Barton’s work often manages to extrapolate one into the other, despite the sometimes restrictive specificity and material concerns of these different practices.Comprising modular, often rectilinear forms, there is a particular softness in the way Barton’s jewellery bends and adapts to the wearer’s body. The artist notes that these works “resemble both the aesthetic of half finished buildings, steel skeletons exposed, and fragile spider webs with multifaceted, slightly different angles glinting.”

An effigy of the jewellery in the installation, Barton’s animations (also featured in the installation) describe, in a very analog manner, how she thinks about and visualizes object making. The animations illustrate how her jewellery objects are designed to move and encapsulate space. In effect this is privileging the viewer to the “3D object caught in the 2D plane of paper and ink”, statically jumping and moving: embodying the potential that only the jewellery wearer can unlock.

Kate Barton is an Auckland based artist. Image courtesy of Objectspace.

-

Speaking In Ramas

“Numismatology, pharmacology and archaeology have been reformed. I understand that biology and mathematics also await their avatars…. A scattered dynasty of solitary men has changed the face of the world. Their task continues. If our forecasts are not in error, a hundred years from now someone will discover the hundred volumes of the Second Encyclopedia of Tlön.”

– Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, 1962.When I heard the title of this new painting installation by Kirstin Carlin and Krystie Wade, I was momentarily confused as to whether I was meant to be associating the ‘Rama’ in Hindu mythology, or the ‘–rama’ in panorama and diorama. In some sense both are equally applicable, as painting, even in its most factual moments, is able to freely dip into fiction or mythology, often embodying a Borges-like feeling of empiricism and liminal exploration.

Confusion about the meaning of the exhibition title was doubtless not the point they were intending, as I know both artists are aware the painted panorama is a peculiar moment in both history and art history, so it was most likely this definition. Anyhow, the conjunctive apprehension of multiple usages, as suggested above, is perhaps a fitting analogy for the exhibition, Speaking in Ramas, for reasons that will follow.

Prior to the advent of photography and the moving image, the painted panorama was a significant and popular simulacrum of the real (and imagined) world in nineteenth century Europe. The most impressive of these were installed in gigantic purpose-built circular rooms replete with artificial fragrances and breezes to stir the imagination and satisfy the vogue for ‘Grand Tour’ experiences. The visitor would enter the panorama via a staircase and be greeted by a handrailed circular viewing platform and a dizzying, continuous painting surrounding the platform.

The paintings produced by surveyors and botanists which were used to peddle the idea of immigrating to New Zealand, paintings which we now hold dear within institutional collections, would have seemed tame by comparison to the fecundity of the panorama which was then all the rage in European cities. Until photography and the moving image, painting was considered as much a mechanical art as a tool for the imagination. The panorama amplified this view, accentuating the desire of many people for instantaneous travel to historically poignant places and past events.

More recently photography has been employed in the realisation of these often massive panoramas, but painting remains of course the only tool appropriate for conveying the information at such a scale. Although panorama painters often relied on technologies like photography and the camera obscura to capture the sense of a real place, just like those early panoramists Carlin and Wade also draw upon the imagination and a plethora of images (now freely available online) to imagine their own places. Although not recreating the 360 degree panoramic spectacle in their works for Speaking in Ramas, both artists have nonetheless engaged with the manner in which panorama pulled together elements that could not be seen in a single painting or photograph.

Having attained a similar command of the ‘hairy stick in mud’, as our art school lecturer once described it, several years down the track into their respective careers Carlin and Wade are ensconced within the mutable history of painting. Both artists, in their own way, envisage panoramic mise-en-scènes using a variety of techniques and mediums in their drawing and realisation processes.

Carlin’s latest paintings utilise Google image searches in a series of works which here interpose the Christchurch Botanic Gardens with the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, London. It is an effort by the artist “to create [her] own fantasy gardens”. Bringing together elements that, like the panorama, are “isolated or scattered around an area too vast to be perceived in one go,” Carlin revisits the conservative vision that Europeans had for New Zealand cities with her own eyes, prompting the viewer to wonder whether new vistas need not always be a glass, stone and concrete simulations of another place, but perhaps have just a strong a validity when their representations emerge merely from flights of the imagination.

Wade’s paintings combine all the twists and tangles of the three dimensional landscape, drawing the viewer into an experience of imagined natural settings that exist within the frame of the canvas. The feeling of movement is an intentional characteristic of her works, which often feature plateaus and garden elements haphazardly linked into path-like constructions, drawing the viewer around a space deliberately held within the constraints of the canvas. Wade quotes the artist Laura Owens: “It’s odd to think of paintings as static, they are so much more. They don’t move like film but seem to have a lot more movement than photography.”

Digital technology, with its potential to faultlessly distort the truth captured within photographic images, often uses drawing and painting inspired ‘tools’ within computer applications like Photoshop, and as such seems to have loosened the captivating, alchemical mantle that technologies such as the panorama and photography originally displaced, but could not replace, from the medium of painting. In as much, the majority of digital drawing technologies used to manipulate images do not seem to have moved beyond emulating collage-like drawing and photographic retouching techniques.

If digital media has freed or reinvigorated public perception of the painting, it also seems to be responsible for other ‘mechanical’ or ‘technical arts’ regaining status in the challenging and decidedly panoptic world of contemporary fine art. It is not uncommon now, for instance, to see ceramic, textile and jewellery practice exhibited alongside painting and installation art within contemporary art galleries and major exhibitions. The panorama may no longer be relevant as a specific optical technology but the role it has played and the influence it still represents remains omnipresent.

Matt Blomeley

07 February 2009– Speaking In Ramas is a new exhibition at Physics Room gallery in Christchurch, 18 February – 14 March 2009.

– Image courtesy Kirstin Carlin and Anna Miles Gallery.

-

Pests in the Tool Shed

The colligate relationship between material, skill and local identity is something which holds particular gravity in the object making scene. There is for good reason for this, as creative practice would be all the poorer were we limited to makers whose modus operandi is international in scope yet oblivious to the rich vein of potential inherent in local history and materials. This relationship to material is often slightly obsequious in the contemporary arts, yet a small number of New Zealand artists in recent years have managed to successfully blaze a path which blurs the line between craft and contemporary art. Whether or not intentional, it would appear that material has reasserted itself as a central factor in our understanding of many arts practitioners and two fine artists that have a foot in this particular canon are Regan Gentry and Ben Pearce.Based in the Hawkes Bay region of New Zealand, Ben Pearce’s practice is testament to an inherited compulsion for tinkering and making. Pearce has made a name for himself though a consistent stream of exhibitions over the past few years. On exhibit have been a range of unusual sculptural objects that you would not be likely to find elsewhere. These objects are more often than not comprised of various timbers that have been crafted into smooth and sinuous forms and then skillfully combined with locally found objects and occasional small machinery components.

Pearce’s ever expanding and evolving repertoire of works is inspired by childhood and suggestive of mostly harmless cyborg-like beings that have perhaps willed themselves to life by employing the detritus and abandoned things found in a disused shed. In his 2007 window installation at Objectspace in Auckland, titled Mr Moorhouse’s Garden, the artist collated a menagerie of retro toy inspired sculptural objects.

Featuring funnel-esque wooden appendages that resembled early hearing aid devices or ‘His Masters Voice’ gramophone speakers, the objects in Mr Moorhouse’s Garden were arranged so as to advance the notion that they were communicating with one another. Pearce noted that they were “solemn and lost, yet in search of each other for cues and dialogue”. Pearce’s upcoming March 7 to May 17, 2009, exhibition at Hawkes Bay Museum and Art Gallery in Napier, Utterance, promises a selection of intriguing new works that expand upon his earlier premise.

Regan Gentry is a contemporary fine artist whose range of exhibition projects has investigated the ingenuity, DIY ethos and colonial history of New Zealand. Gentry’s 2007 series, Of Gorse, Of Course, exhibited at the New Dowse and The Sargeant Gallery, featured an exhaustive selection of works, all of which were fashioned from gorse. Imported to New Zealand during colonial times as a hedge, gorse doggedly spread its way around the country fast becoming a nationwide pest. Conceived during his four months in Invercargill as a 2006 William Hodges Artist In Residence, Of Gorse, Of Course drew attention to Gentry outside of the regular art channels as much for the variety of objects on display as the artisan skills displayed by the maker.

There is a vein of dry wit running through all of Gentry’s exhibitions, in particular with the Gorse series, which communicate particular mannerisms and gung ho nature of the antipodean lifestyle. Other recent works by Gentry have included several major public sculpture commissions as well as a 2008 exhibition for the Sargeant Gallery in Wanganui, Near Nowhere, Near Impossible, developed while he was 2007 Tylee Cottage artist in residence.

Matt Blomeley

23 January 2009Images above by Regan Gentry (top) and Ben Pearce (Bottom)

Writing commissioned by Object

Ben Pearce website http://www.benpearce.co.nz/ -

Two new Objectspace installations to check out

Best In Show 2009

Best In Show is Objectspace’s fifth annual exhibition in a series which showcases a handpicked selection of outstanding craft and design graduates. The Best In Show format has proven itself to be an important event within the annual craft and design exhibition calendar and Objectspace is proud to have represented a range of new voices over the last five editions of Best In Show. The fourteen exhibitors in this year’s exhibition encompass the exciting and varied terrain of spatial, graphic and textile design along with ceramics, jewellery and object art installation.

Previous Best In Show exhibitors have moved on to win design awards and competitions, establish themselves within their chosen fields and some are already moving into roles as mentors and teachers. If there is a theme or feeling that stands out among these fourteen exhibitors in 2009, it is that critical engagement is positioned foremost within their varied practices in conceiving and making intelligent objects.

Jacqui Chan’s Exotic Blend

A reflection upon cross cultural heritage, Jacqui Chan’s Exotic Blend signifies her desire, as a contemporary jeweller, to embody the particular form of chinoiserie endemic to her New Zealand upbringing.

The artist notes that “growing up initially in bicultural Whakatane and later the homogenous Pakeha-dominant South Island, there was little reflection of our Chinese half in life outside our home. It was therefore somewhat natural that our sense of Chineseness became entwined with domestic objects. Rice pattern bowls, our Chinese teapot, painted fans, shitake mushrooms, and the mahjong set were day-to-day evidence of our cultural heritage and imagery with which to imagine China.”

With this body of work Chan was drawn to tea tins for the symbolism they engender. The exotic imagery depicted in tea tins is, she observes, equally distant from modern China as it is from England. Cut up, pierced, folded and tricked into wearable brooch forms, the tea tin is reclaimed by the artist.

Jacqui Chan is a New Zealand artist. Trained as an architect and then a jeweller, she will be undertaking doctoral studies in Australia from 2009.

-

‘Special Needs’ post at Paua Dreams

Moyra Elliott just informed me of an excellent post on Damian Skinner’s Paua Dreams website that I’d almost missed the last time I was checking out his site. In his post, Skinner addresses the issue of craft artist representation within the contemporary art world. The answers to this problem are definitively buried within the scope of each craft discipline and it does appear, as Skinner points out, that jewellers are currently playing the contemporary ‘art game’ more successfully than ceramists, glass and textiles artists.

As Skinner illustrates, the issue is relatively simple: with the exception of several contemporary art galleries that represent a select few jewellery makers, craft focused dealer galleries – the predominant exhibiting venue for jewellers – in NZ are usually a little out of tune with the workings of the contemporary art system. I won’t be surprised when when a ‘maker’ breaks through to Walters-type acclaim, but in the current climate it’s more than likely that it won’t be someone singled out from a craft gallery exhibition alone.

Sarah Sadd of Masterworks may have had to feel Skinner’s heat in relation to this issue (refer to the post), but Damian is in no way discriminating against the importance of galleries such as Masterworks. I can’t think of a better way to describe the current situation as when he summarises: “Either craft plays the fine art game so it can be eligible for the Walters Prize, or the Walters Prize (and the art world that sustains it) is transformed and old hierarchies are dismantled. To imagine otherwise is naïve, and that just gives fine art another reason not to take craft seriously.”