Posts relating to arts projects (writing, curating, etc.)

-

Design related reading list

As I’m working on a new design exhibition, a bit of a tidy-up list was needed. I compiled the following from books lying around at home, in my public library record’s reading history and on my kindle iphone app:

– The Craftsman / Richard Sennett

– The art of the commonplace: agrarian essays of Wendell Berry / edited and introduced by Norman Wirzba

– Cradle To Cradle / William McDonough and Michael Braungart

– Sustainability by Design: A Subversive Strategy for Transforming Our Consumer Culture / John R. Ehrenfeld

– In the bubble: designing in a complex world / John Thackara

– The design of future things / Donald A. Norman

– Deluxe: how luxury lost its luster / Dana Thomas

– Evocative objects : things we think with / edited by Sherry Turkle

– The evolution of useful things / Henry Petroski

– Massive change / Bruce Mau with Jennifer Leonard and the Institute Without Boundaries

– The human factor: revolutionizing the way people live with technology / Kim Vicente

– Pushing the limits: new adventures in engineering / Henry Petroski

– Toothpicks and logos: design in everyday life / John Heskett

– Twenty-first century design: new design icons from mass market to avant-grade / Marcus Fairs ; foreword by Marcel Wanders

– Design for sport / edited by Akiko Busch

– Techno textiles: revolutionary fabrics for fashion and design / Sarah E. Braddock and Marie O’Mahony

– The artificial kingdom: a treasury of the kitsch experience / Celeste Olalquiaga

– The AZ of modern design / Bernd Polster … [et al.]

– It must be beautiful: great equations of modern science / edited by Graham Farmelo

– Nature in design / Alan Powers

– Beautiful Code / Edited By Andy Oram and Greg Wilson

– 97 Things Every Programmer Should Know / Edited by Kevlin Henney

– Our Choice: A Plan To Save The Climate Crisis / Al Gore

– Earth in the balance: ecology and the human spirit / Al Gore

– Design culture now: National Design Triennial : Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution / Donald Albrecht, Ellen Lupton, Steven Skov Holt

– Ecodesign: the sourcebook / Alastair Fuad-Luke

– At home: a century of New Zealand design / Douglas Lloyd Jenkins

– 40 legends of New Zealand design / Douglas Lloyd Jenkins

– The reinvention of everyday life: culture in the twenty-first century / edited by Howard McNaughton and Adam Lam

– Hiding in the mirror: the mysterious allure of extra dimensions, from Plato to string theory and beyond / Lawrence M. Krauss

– How mumbo-jumbo conquered the world: a short

history of modern delusions / Francis Wheen

– Design art: on art’s romance with design / Alex Coles

– Design – is not equal to – art: functional objects from Donald Judd to Rachel Whiteread / Barbara Bloemink and Joseph Cunningham

– The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Design Since 1990 / Guy Julier -

Leonor Hipolito at Objectspace

An Objectspace summer window installation by Portugese jeweller Leonor Hipólito, Apparatus comprises a range of works reproduced after medical tools and fashioned out of tree trunks and branches. Delicately hand made, allowing the wood grain and shape to subtly influence the final form, these ‘tools’ serve as reminders of our relationship to the natural world.

Apparatus embodies a very timely appeal espousing both environmental and artistic concerns. Hipólito quotes conceptual artist Josef Beuys, who said: “For a certain period of time, we still have the possibility of making free decisions, the decision of taking a path that is different from the path we took in the past. We still can decide if we want to align our intelligence with nature.”

Leonor Hipólito is a contemporary jeweller based in Lisbon, Portugal. A graduate in Jewelry at the Academy Gerrit Rietveld (Amsterdam) in 1999 and winner of the Gerrit Rietveld Prize, she exhibits internationally and has featured in a number of symposiums and triennials.

-

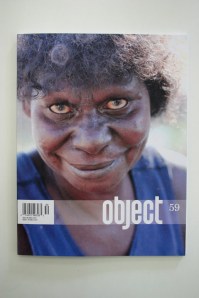

In From The Garden review

Object magazine (Issue 59) featured a review of In From The Garden, by writer Jo Tresize.

-

Carving: Patrick Lundberg

It seems every young kid is destined to undertake certain ill-conceived acts and then remain ashamed of such activities well into adulthood. This kind of lingering shame would hopefully indicate an aversion from a future life in crime for the majority of us. An example: Hacking into my mum’s painting easel with a knife. what was I thinking? It was the early 1980’s and I was an easy-going country kid; a typical boy who fished for eels in the creek over the road and a keen reader who was also into drawing and painting. Trucks, animals, family members, houses, cartoon characters, etc; I drew them all. This predilection towards art makes the vandalistic action upon a painting easel appear slightly ironic.There is probably a Freudian case study which would explain my one or two lawless acts during these years. For example, the easel from Freud’s perspective is possibly an untouchable ‘clan totem’ (1) from my childhood. In some sense the easel predestined my attendance at art school by twenty or so years. What then of hacking into it with a pocket knife? Fortunately I wasn’t born of a different era or locale; Freud notes the totem is accorded utmost respect among worshippers; in past ages violations of ‘totem taboos’ met with with harsh consequences, to say the least. (2)

In as much as it could have been the spirited rebellion against a taboo, or understandable frustration in not being able to use my mother’s oil paint with the same virtuosity as a felt tip pen, it was not in this instance an act of anger or frustration. I believe now, as I did then, that this action was simply the intoxicating combination of an exotic and unobtainable looking material meeting a pocket knife blade.

Although no longer able to visually recall hacking into this easel, I still respond viscerally from the incident – even following an art school education – to the notion of carving into something permanent or solid. The easel, thirty or so years later still in regular use by my mother, was the first thing I thought of when I came upon the art gallery wall carvings of Patrick Lundberg in 2006.

The transience of Lundberg’s work, in that these carvings, or excavations, will happen for a short period of time and disappear with the first swipe of polyfilla, imbue viewers with the feeling that despite the limited time frame of an artists gallery showing, his works – being as they are ‘carvings’ – are something other than temporary. Fittingly, the walls of rm103 gallery in downtown Auckland still bear the faint shapes of Lundberg’s 2006 exhibition, as he recently pointed out to me at a gallery opening. Whether or not this story relays an intentional aspect of these works is not really the point, but it illustrates the sense of permanence the viewer may experience as an immediate response to Lundberg’s work.

Lundberg’s wall carving work is predominantly destined to occupy a concept of temporality, although this is not entirely related to the time alloted an art exhibition. Foregrounding the temporality in Lundberg’s work is the recent emergence of a culture within many presenting institutions and major public museums for the authentic and live experience. This is of course an addition to the regular presentations of new and old ‘pre-approved’ objects. The nature of the live experience however is that it is almost lost before it began and so the historical moment passes irretreviably.

While not suggesting a criticism of this institutional framework, to the regular patron of an institution Lundberg’s work in a sense bridges the gap between the varying degrees of dialogism captured in an institution’s past exhibitions, and the currently popular souvenir-like live event. The process of skillfully marking and cutting the outline of a drawing then delicately removing strips of paint from the gallery wall uncovers stratified layers from previous exhibitions and often previous artists site specific wall works; all within a precise and site specific drawing. (3)

This brand of virtuosity with a scalpel blade suggests the continued potential and importance of painting in conceptual art and critical theory. Lundberg is ungrudgingly attempting to engage with multiple possibilities. At the same time, it appears – despite the different intellectual references – that he relishes the opportunity and sentiment of digging his way through various histories of the institution, at least as much as I secretly enjoyed hacking into an easel with a knife.

Matt Blomeley

1. Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo, The Return of Totemism in Childhood, Routledge Classics, 2001, London, (pp120). Quoting from J.G. Frazer’s Totemism and Exogamy (1910), Freud suggests there are “at least” three kinds of totem, “(1) the clan totem, common to a whole clan, and passing by inheritance from generation to generation; (2) the sex totem, common either to all the males or to all the females of a tribe, to the exclusion in either case of the other sex; (3) the individual totem, belonging to a single individual and not passing to his descendants…”

2. ibid, “The rules against killing or eating the totem are not the only taboos; sometimes they are forbidden to touch it, or even to look at it; in a number of cases the totem may not be spoken of by its proper name. Any violation of the taboos that protect the totem are automatically punished by severe illness or death” (pp120)

3. Wright, Richard, Richard Wright, Richard Wright and Thomas Lawson in conversation, Milton Keynes Gallery, UK, 2000. Wright observes of his painting practice, which displays an interest in site specificity similar in some respects with Patrick Lundberg, “It’s not so much about the individuality of ideas, but the quickness of how an idea gets translated through the agency of something like skill. It’s karaoke shit really. The sheer dumbness of trying to transmit something through your own body – being forced to find definitions. The agency of this kind of manoeuvere that, against the odds, allows you to come up with the goods.”

-

Overheard Conversation

An abiding interest in topiary (hedge and shrub sculpture) is one distinguishing feature of American ceramic sculptor Scott Chamberlin’s artistic practice. Topiary, of course, is a complex and long held tradition involving the trans-generational maintenance and subtle grooming of living plants into various shapes. Many active topiary gardens in Europe predate the colonization of New Zealand not just by decades, but by hundreds of years.It is fitting given his commitment to topiary that Chamberlin, a Visiting Professor in the Contemporary Craft Program, Unitec in 2009, during the course of his artist residency in Auckland has closely observed – and taken inspiration from – the many unusual plant forms that make up our flora and fauna. The title of Chamberlin’s Objectspace Vault installation is suggestive of the approach he has taken with his studio practice while in New Zealand.

Like a witness to an ‘overheard conversation’ – the conversation being New Zealand’s Diaspora of recently immigrated peoples and our relation to the landscape – the new works that have resulted bear traces of his present inspiration but they also lean on his experiences as both sculptor and topiarist.

Extracting reproductive forms and other attributes from our foliage, in these new works the native forest of New Zealand and our engagement with it is investigated with fresh eyes. Chamberlin has created a terracotta landscape combining plant-like elements with subtle and erotic forms suggestive of the body.

Chamberlin observes of his New Zealand muse: “One can see acknowledgement of many visual remnants of my impressions of NZ. One will see wigged (colonial) people, one will see foreigners, one will see ornamentation (from a European perspective) one will see my response to a bewildering verdancy… much flora and fauna, some “native” and some not. One will see some pondering of what “native” means to varying constituents.”

Mark Masuoka, Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art/Denver, has observed that Chamberlin “continually mines a rich vein of ideas by fusing material sensuality with a tactile consciousness and the pleasures of spontaneity. The structural clarity displayed enables the viewer to experience the presence of the object with a ritualistic simplicity. His lush, voluptuous forms are clearly not utilitarian, but function in defining internal as well as external space.”

Scott Chamberlin is the 2009 Visiting Professor/Artist in Residence at the Department of Design, Faculty of Creative Industries and Business, Unitec, as well as international judge of the 2009 Portage Ceramics Awards. Snowhite Gallery at Unitec is showing Fertile Matters, an important solo exhibition of Chamberlin’s work (until 19 October.) Chamberlin was born in California in 1948 and holds a Masters Degree from Alfred University. He has featured in numerous US and international exhibitions and is currently a Professor in the Department of Art & Art History at the University of Colorado. Chamberlin is the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts awards (1990, 1996) as well as a prestigious Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant in 2001.

What: Overheard Conversation

Where: Objectspace

When: 22 September – 7 November 2009(Unitec studio image courtesy Scott Chamberlin.)

-

Gilded Blessing

Writing of his classical musical training as a cellist, Richard Sennett observes “the development of any talent involves an element of craft, of doing something well for its own sake, and it is this craft element which provides the individual with an inner sense of respect. It’s not so much a matter of getting ahead as of becoming inside.”Employing differing art forms, Gilded Blessing (the cello is a Chinese ‘Blessing’ brand) is a collaborative audiovisual installation between gilder Sarah Guppy and composer Eve de Castro-Robinson. Both were attracted to the idea of exploring the musical instrument as a metaphor and a conduit for traditional artisan skill and contemporary sound practice.

Gilded Blessing has been configured so that while near the cello, the viewer taking in the sensuous gold gilded form simultaneously informs a proximity monitoring camera. In some sense the viewer is able to ‘play’ the cello in the act of moving around but not actually touching it.

An integral part of this project is not only the craftsmanship, but also the musical instrument as a performance object. Eve de Castro-Robinson has composed 9 melodic phrases for the cello. It is these electronically manipulated ‘blessings’ which the viewer is able to activate and take in while in the intimate presence of the finely hand-crafted object.

Eve de Castro-Robinson is a critically acclaimed New Zealand composer whose works have been performed internationally. Twice winner of both the SOUNZ Contemporary award and Philip Neill Memorial prize awards, she was awarded the CANZ Trust Fund award in 2000.

Sarah Guppy is a gilder and painter. Trained in the UK where she worked on the Royal Collection among many other prestigious projects, she has over 25 years experience and is an exhibiting painter with work in collections in the UK and New Zealand.

What: Gilded Blessing

Where: Objectspace

When: 17 September – 4 November -

Review of In from the Garden

Damian Skinner writes: “The introductory wall text for this exhibition says that it is about two main issues: ‘the skilled terrain of craft practice’ that is related to, but not the same as, fine art; and the way in which Objectspace can intervene in the craft sector and support newish makers. The second appears to be the major impulse behind the show, with the text making it clear that ‘In from the garden is intended to look closer at four makers from around New Zealand who, currently at this period in their respective careers, are staying the course and readying to settle in for the long haul.’ The four are jewellers Renee Bevan and Victoria McIntosh, ceramist Blue Black, and sculptor/woodworker Ben Pearce.

Talking of practical things first: the show is nicely installed in the gallery. There is not a huge amount of work – I counted sixteen individual works, some of which are made up of groups of objects – and the gallery feels spacious, but it doesn’t feel underdone or empty, either. Sensibly I think the curator Matt Blomeley has recognised the conceptual and visual complexity of a lot of these objects, and given them plenty of space.”

For the full interview visit Skinner’s Paua Dreams website. Published 7 August 2009.

-

Kirsty Lillico: I Came Back As Someone Else

As endless streams of fashion advertisements, globalized brands and chain stores attest, the enormous variety of social functions involving garments are easy to overlook. Through dress and fashion we perform many roles but among the most important are to project confidence whilst protecting insecurities, physical or otherwise. Kirsty Lillico’s textile-based sculptures address this duality and also act on a deeper level, as prompters, reminding the viewer of garments additional abilities to either bottle-up or externalize our perceived individuality.

As endless streams of fashion advertisements, globalized brands and chain stores attest, the enormous variety of social functions involving garments are easy to overlook. Through dress and fashion we perform many roles but among the most important are to project confidence whilst protecting insecurities, physical or otherwise. Kirsty Lillico’s textile-based sculptures address this duality and also act on a deeper level, as prompters, reminding the viewer of garments additional abilities to either bottle-up or externalize our perceived individuality.Working with an entirely white palette, Lillico’s textile sculptures include utilitarian objects such as mittens, helmets and capes. Presented alongside this are garment-like objects which “have ceased to be a ‘second skin’ for the body, and instead have become the body itself.” She describes this aspect of her work as representing both “the suppression of individuality, and its preservation. This contradiction is intended to activate curiosity in an audience regarding the social and psychological context for the garments use and manufacture.”

It is appropriate given the subject of Lillico’s works and their resemblance with modern fashion that the viewer of these art objects is possibly attracted to the notion of embellishing or cocooning oneself within them. As writer, Katy Corner, has observed, Lillico’s sculptures are “full of potential and anticipation. They project a powerful, intelligent presence as if patiently waiting for their use to be discerned and appreciated. They also seem to be waiting for us to do something, handing over responsibility.”

Kirsty Lillico is a Wellington based artist. She holds an MFA from RMIT University, Melbourne.

What: Kirsty Lillico: I Came Back As Someone ElseWhere: Objectspace Window, 8 Ponsonby Rd, AucklandWhen: 23 July – 16 September 2009 -

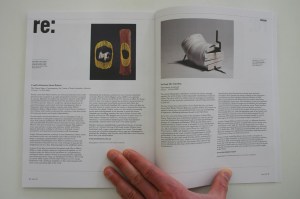

Handstand: Unfamiliar and Innovative Contemporary Jewellery

Notes on the Top Mark and Resene Award Winners

The first four years in a contemporary jewellery career is a pivotal time. Inevitable and obvious issues confront the maker head-on; finding gallery representation and supplying proven selling pieces, not to mention holding down a day job. These exterior aspects of a practice push and pull new makers in perhaps unexpected directions. Although by no means insurmountable, challenges like this serve to define the committed versus those who will inevitably fall off the radar. A small yet vibrant part of the visual arts sector, contemporary jewellery has grown exponentially in recent years and witnessed a number of New Zealand practitioners establishing national and international reputations. The makers showcased in Handstand provide a fantastic snapshot of just a few talents emerging out the handful of tertiary education programmes in this field, from around the country.

Top Mark Award winner Vaune Mason’s unique work, Control, stands out with its consideration of the jewellery wearer. An intriguing and nostalgic object, the work is not what you would consider typical jewellery. A vintage-looking object resembling a mourning jewellery locket, or a ‘box brownie’ camera, and finished with a sensible leather strap, the wearer of Mason’s work engages in a conceptual manner with the object. In choosing from a selection of portrait images, one of which then peers out of the lens-like porthole, the viewer is perhaps left to ponder; is this a metaphoric device providing us the ability to capture our mood (like a camera) or is it suggesting that one can choose who we mourn on any given day? The truth is slightly different, as the images are of Mason herself, who explains: “I have given over my physical identity as well as my ‘marks’ to this piece. The new owner, over whom I have no control, will be able to decide how I am viewed. They may never meet me in person, but with this piece, they can see an intimate side of me.”

Second place in the Top Mark awards went to Vivien Atkinson, whose series Suite: Illusions addresses bridal jewellery. A universal symbol, the ‘bride’ is synonymous with beauty, purity and of course the always implied air of temporality. In transferring the fragile and undoubtedly highly skilled craft of cake decorating to jewellery, Atkinson engages directly with the discussion of adornment, an issue which resounds more strongly in contemporary jewellery than other art practices.

Winner of the Resene Award, Jhana Miller’s The Charm Bracelet is a witty work which highlights our contemporary obsession with disposable consumer goods. This colourful collection of charms is ironically fashioned from the eminently more recyclable and un-jewellery-like medium of paper.By the time they have ‘made it’ those who thrive in contemporary jewellery can be considered successful as both fine artist and skilled craftsperson. The emphasis on craft skill is something which needs to be asserted here: skill, in combination with fresh ideas and cogent aesthetic explorations that is. As writer and curator Damian Skinner discusses in his essay (the publication accompanying Handstand will include essays by Damian Skinner and Kevin Murray), developing skill takes time. Skill of course cannot be acquired via a certificate and it takes many years of hard graft in the studio to – hopefully – master the nuances which add the indiscernible polish that can define a successful craft practice. These makers are proving beyond doubt that they are well on their way.

Matt Blomeley (2009 judge of the Top Mark and Resene awards)

HANDSTAND: Unfamiliar and Innovative Contemporary Jewellery

Exhibition dates: 16 – 19 July 2009

Sky City Convention Center

The New Zealand Jewellery Show

www.jewelleryshow.co.nzCurator Peter Deckers (educator and established contemporary jeweller from Wellington) has brought together the Handstand exhibition, featuring the latest works from participating emerging jewellery artists in a variety of artistic styles and media.

-

Printing Types: New Zealand Type Design Since 1870

Printing Types: New Zealand Type Design since 1870

The word ‘Designer’ is a loaded term which for most of the population inspires visions of glamourous personalities, high fashion and covetable objects. Let’s face it, the glossy and multifaceted world of design has held us enthralled for decades. Within the varied sub-industries of design however, there are numerous career pathways that garner relatively little public acclaim, despite occupying important roles within contemporary society. Type design is one of these roads less travelled.For these reasons it was rather surprising that a hit feature at the 2007 Auckland International Film Festival was – you probably guessed it – all about type design. Gary Huswit’s documentary Helvetica was a runaway success documenting the use, abuse and global popularity of this now ubiquitous typeface. Helvetica attracted numerous attendees, many of whom probably hadn’t paused for long to consider the history and of a typeface we most often turn to when composing the majority of our daily correspondences.

So where do we fit into this picture here in New Zealand? Does our local type design history consist of Koru motifs, borrowed and embellished ad infinitum? The answer is that this kind of perception couldn’t be farther from the truth. A small and discerning industry with many entertaining and intriguing stories of design success and failure, the history of type design in New Zealand has unfortunately been inadequately documented. Designer and curator Jonty Valentine aims to do something about this.

Printing Types: New Zealand Type Design Since 1870 is a new exhibition and publication project at Objectspace. Having previously curated the outstanding 2006 exhibition at Objectspace, Just Hold Me: Aspects of NZ Publication Design, Jonty Valentine has this time researched and compiled a selection of key moments and narratives in local type design from a history spanning approximately 140 years. An important and timely project to undertake, he says “it is remarkable how un-heroic and invisible the history of type design has been here”.

Valentine observes that “the purpose of this project is to begin to establish, or at least begin to lay the case for such a series of stories” and to question “why there is so little written about this subject.” Objectspace Director, Philip Clarke, has overseen both of Valentine’s exhibitions and notes that “Printing Types, is I believe, the first exhibition and related publication completely focused on contemporary and historical New Zealand type design.”

Two highlights of Printing Types include the 1960s achievements of internationally celebrated New Zealand-Samoan Joseph Churchward who is the subject of a new book, Joseph Churchward (ed. David Bennewith, published by Clouds, 2009) and Tom Elliott (designer of the iconic 1970s Air New Zealand typeface).

Contemporary type designers in New Zealand featured in the exhibition are exemplified by designers such as Kris Sowersby and more speculative practitioners like Luke Wood, who are producing work of great intelligence and wit. The result of these projects is sometimes taken far beyond what the designer originally intended. For instance, Wood’s McCahon typeface (2000) has had a very eventful life which highlights the value of typefaces as commodities. In its short life it has been appropriated by a multinational, found its way onto ‘Charlie’s’ fruit juice bottles and been used in the branding for an important Colin McCahon exhibition!

Other exhibitions: Coinciding with Printing Types is an Objectspace Window installation by contemporary artist Kirsty Lillico. Also on display will be an intriguing new Objectspace Vault installation of tea vessels.

What: Printing Types: New Zealand Type Design since 1870

Where: Objectspace, 8 Ponsonby Rd, Auckland

When: 25 July – 12 September 2009.

Gallery hours: Tues – Sat, 10am – 5pm. Free admission.

Publications: A catalogue (66 pages) and typeface specimen posters (A0) for this exhibition will be available for sale at Objectspace

Curator’s talk: 11:00am Saturday 1 August 2009 at Objectspace

Image: Luke Wood, McCahon (detail), typeface design, 2000.