A favourite holiday novel of mine returned to several times over the years is set in an idylic university town. There is of course something asmiss with this place, not that many locals would even notice: a powerful spiritual presence lingers in the surrounding landscape. To the few who are destined to see it, this admirable yet malevolent looking character takes the form of a giant black domestic cat, cursed by a local witch to linger around the town and its surrounding hills. (1)

The spell which binds the old tomcat to the town is also an invisible leash, occasionally tripped over when visitors to the town and locals happen to cross his path. The central character in the story becomes entangled with the cat in this manner. She meets him again after passing to the ‘other side’ and, upon discovering his endless multitude of physical forms, has the following conversation with him: “ ‘Schrödinger’s cat!’ ‘That’s only a concept, more than that.’ Was it against the law of the universe for anything to be only what it seemed? ‘Nothing is against the law. The law is its own violation. That is the core of all events, that is Schrödinger’s cat.’“ (2)

Heavy dialogue for a popcorn novel, which no doubt passed right over my head as a teenager. I was surprised, in returning to the novel recently that it would actually have some relevance to me as an adult reader. The common superstition, explored in this novel, that we are predestined to a certain path (that can even account for when fortune or misfortune prevails upon us and we are confronted by our ethics in making decisions!) returned to me upon visiting Bronwynne Cornish’s ceramic studio and considering her most recent work.

Fortunate to undertake a 2008 residency in India, this experience has greatly influenced Cornish. Speaking about one of the repeating forms that is due to feature in her 2009 exhibition at Masterworks gallery, she relayed to me the story of a remarkable place in India, which she was unfortunately unable to visit first hand during her time there, for logistical and geographical reasons. In this place is a library that apparently holds a detailed pre-written record about anyone who wishes to know their path or fortune in life.

Cornish’s shapeshifting works, related to the story she told me – reminding me of the karmic premise as well as the imposing creature of my novel – are a series of six legged beings. Standing proud on four solid, powerful looking legs, their arms with palms cupped together servant-like hold forth your fortune cards. Although there is an overhanging air of mysticism to these works, Cornish is offering more than just an effigy of ethereal worlds and beings. Her investigation also concerns the present, the future, and our place in it.

The maker of ceramic objects which literally wear the skin of her subject(mysticism), like an unbiased contemporary theologian holding the subject of religion at arms length, Cornish explores in-depth and with an open mind the desperation with which we sometimes cling to beliefs and presumptions that have been held for millenia, all the while looking for underlying questions. The questions, and possibly answers, that Cornish is posing with these works are deliberately left open for the eyes and minds of the viewer to ponder and decode, as she is not presumptuous enough to suggest otherwise.

Of any subject or idea that comes to mind upon considering Cornish’s new works, perhaps the most important is the notion of Self. Philosopher Slavoj Žižek observes that “if we penetrate the surface of any an organism and look deeper and deeper into it, we never encounter some central controlling element that would be its Self, secretly pulling the strings of its organs … there is effectively no self … A true human Self functions, in a sense, like a computer screen: what is “behind” it is nothing but a network of “selfless” neuronal machinery.” (3)

To know that ones Self is not governed by something other pulling its ‘strings’ is refreshing, yet it does not negate the enjoyment of lyrical objects, which often engage in a language that predates western science and philosophy. Cornish’s works operate interestingly and fluently in this context; contemporary objects – enjoying a growing, appreciative audience – in an age where it is more common to see artists exploring science and genetics than pre-European belief systems.

Bronwynne Cornish’s years of pushing clay through her fingers are combined with intriguing ideas and relevant subjects to make a convincing artistic statement, reminding one that we each exist as a conflation of our bloodlines and our learned experiences. As Žižek notes, “what makes me “unique” is neither my genetic formula nor the way my dispositions were developed due to the influence of the environment but the unique self-relationship emerging out of the interaction between the two.” (4)

Matt Blomeley

8 March 2009

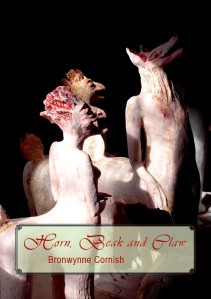

Essay commissioned for Bronwynne Cornish’s upcoming exhibition Horn, Beak and Claw at Masterworks)

1. Strieber, Whitley, Cat Magic, Grafton, London, 1988.

2. Ibid. (pp323,324)

3. Žižek, Slavoj, Organs Without Bodies, Routledge, New York and London, 2004. (pp117,118)

4. Ibid. (pp118)

Leave a comment